Every outdoorsperson should know the nuts-and-bolts of the compass. We live in an age when digital navigational tools abound: GPS receivers, satellite messengers, smartphone maps, and apps.

These are all well and good, wonderful resources to have—but they aren’t foolproof, and overreliance on them without backbone knowledge in tried-and-true map-and-compass wayfinding can leave us in dire straits.

In this article, we’ll introduce the basics of how to use a compass: what the tool does, how it’s put together, and all the invaluable locational and route-finding information it can provide out there in the backcountry.

- Use a compass to navigate by taking bearings and compensating for obstacles.

- Aim off when returning to a starting point in order to maintain course.

- If there's no opposite-side landmark, take a back bearing from the starting point.

- If you hit an obstacle, aim off by veering significantly to one side or the other of your bearing line.

- Practice navigation in different settings to become comfortable using a compass.

Why Should I Learn to Use a Compass?

A compass always has your back, keeping you from going in the wrong direction when navigating through remote wilds. Your smartphone might die, your GPS unit may act up, but that compass of yours—as long as you keep the magnetic needle away from interfering metal—points north through thick and thin. You can walk a straight course and stay oriented even when socked in by a cloud (or caught by darkness).

Now, even as we underscore the tremendous power of a compass, it’s worth noting there’s a surprising amount of sturdy wilderness navigation you can do without one. In many landscapes, experienced outdoorspeople can stay oriented just by matching obvious physical landmarks with their mapped locations.

Using such on-the-ground navigational aids as handrails (long linear features such as rivers, roads, or powerline corridors roughly aligned with your desired course of travel) and catchpoints (mapped landmarks along a handrail that peg your location), you can cover a lot of ground without peeking at your compass.

But the point is, you should have a compass to peek at it if you need it—and, in many situations, using a compass and map together is the surest way to stay on track and avoid getting dangerously turned around.

Introducing the Tool: Parts of a Compass

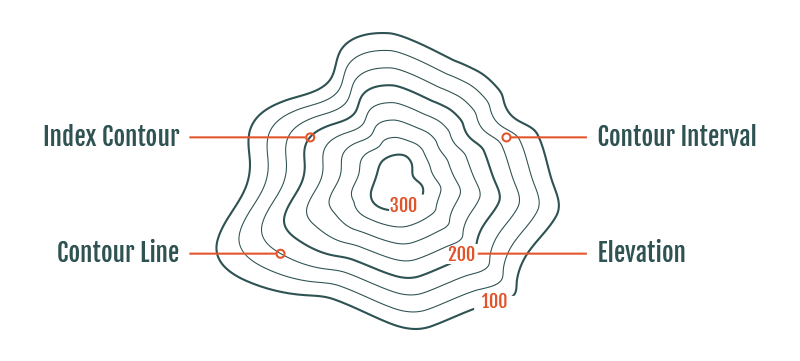

A magnetic compass consists of a freely rotating magnetized needle that lines up with the Earth’s magnetic field, one end of it usually a red arrow pointing north. (We’ll get into just what “north” means in this context shortly.) The needle does its thing within the compass housing, filled with a liquid that dampens the compass needle’s otherwise jittery movement.

Along the rim of the housing or case, the 360 degrees describing a circle come hatched and labeled on a dial (aka azimuth ring or bezel ring). The four cardinal points (cardinal directions)—North, South, East, and West—are labeled at 360 degrees (or 0 degrees), 180 degrees, 90 degrees, and 270 degrees, respectively.

Some compass models denote not only the cardinal points but also the intercardinal points of North East, South East, North West, and South West, and occasionally even finer-scale divisions (North-Northeast, South-Southwest, and other secondary intercardinal points).

Different Types of Compass

The cheapest compasses are fixed-dial models, but, while better than nothing, these aren’t the go-to choice for a dyed-in-the-wool hiker, backpacker, climber, or hunter.

That would be the baseplate compass, also known as the protractor compass given it serves as that tool in mapwork, or as an orienteering compass due to its original invention for use in that sport.

It goes without saying that the same skills competitive orienteer employs are part of a backcountry traveler’s basic route-finding toolkit.

Baseplate Compasses

Baseplate compasses consist of a rotating bezel-set atop a see-through, square-edged base plate. Within the compass case, below that free-swinging compass needle, parallel lines known as meridian or orienting lines can be used to match with the north-south grid lines of a topo map.

At the center of the case and aligned with those meridian lines, an orienting arrow points to north on the compass housing.

The base plate will also typically include a direction-of-travel line or direction-of-travel arrow pointing toward the front edge of the compass. Its back end meets the rotating bezel at an index line. Two or three of the base-plate edges include multiple ruler measurements and scales for determining distances on a map.

Many orienteering compasses include a hinged cover with a sighting mirror. Run through with a line, this design allows you to hold the compass at eye level when pointing toward a target landmark or along a desired bearing, using the mirror (set at about a 45-degree angle) to confirm the direction where the index line meets the dial.

Other Types of Compasses

Now, keep in mind there are a number of other kinds of compasses: the stripped-down thumb compass, non-magnetic compasses such as the gyrocompass, the military-style lensatic compass or magnetic-card compass, digital compasses, and more.

But, given considerations of accuracy, ease-of-use, affordability, and general wilderness suitability, your average outdoor user is going to want to obtain—and, naturally, eventually master—a baseplate model.

For that reason, the rest of this article focuses specifically on baseplate-compass basics.

Understanding & Accounting For Magnetic Declination

Accurately using a compass and a topo map together in most parts of the world necessitates a bit of translation, you might say. The reason is that the two navigational tools actually have their own, different definitions of “north”: Your compass points to a different reference point than your map.

Declination: True North & Magnetic North

The north marker on your topo map refers to true north, aka “geographic north.” True north indicates the North Pole, the ultimate northern reference point we all tend to envision. But the arrow of your compass’s magnetized needle points to a different north: magnetic north.

Compared with stolid, unchanging true north, magnetic north describes a transient location: the northern tip of the Earth’s magnetic field—the so-called “magnetic North Pole”—which actually moves around due to the molten messiness of Earth’s deep innards.

So there are two complications we face when trying to use our compass with our topo map to find our way.

The first is the fact that magnetic north and true north differ. Magnetic declination describes the difference between true north and magnetic north in cardinal degrees. That difference is negligible along what’s called the line of zero declination, where true and magnetic north agree.

But off that line, you need to correct for a west or east declination in order to have your compass needle and map sync with one another. Without proper declination adjustment, your bearings translated between compass and map will be off, which can result in trekking majorly astray.

The other complication is the magnetic north’s roving ways. Many topo maps will indicate their depicted area’s declination via a diagram at the bottom, but this measure changes year by year; that becomes an issue after a while. This speaks to the value of checking your map’s revision date and going with as current an issue as you can.

But thanks to online resources such as the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s declination calculator or the Canadian Geomagnetic Reference Field, you can assure yourself of a thoroughly up-to-date declination adjustment.

Correcting for Declination

Many baseplate compasses offer built-in adjustable declination, achieved with the turn of a screw or some other mechanism. You can also use tape to identify your area’s declination correction or simply go through the math (subtracting or adding degrees per the given declination) when making measurements with a map and compass.

You can also correct for declination on the map rather than the compass by drawing in the appropriately offset lines, but that’s more troublesome; just pay the marginal amount more for a compass with adjustable declination.

If you’re planning a hiking trip in a different geographic region than where you usually go backpacking, remember to check the area’s declination and adjust your compass accordingly before hitting the trail.

All of what follows assumes you’ve corrected for declination on your compass.

How to Use a Compass to Take Bearings

A bearing describes the direction between two points as defined by the angle made by a line run through both locations and a given baseline, which in orienteering work is either magnetic or true north.

You can use a compass to take bearings from the landscape—considering your current position against a visible landmark—or from the map, measuring the angle between two mapped points.

Direct Bearings

Take a direct bearing from a landmark you can see—a mountain peak, a lake, a grand old tree—by holding your compass level at your chest or (with a sighting mirror) in front of your eyes and pointing the direction-of-travel arrow at the feature.

Then rotate the compass housing until the compass needle’s contained within the orienting arrow, and read the measurement where the direction-of-travel arrow meets the dial. That measurement identifies the direction between your current position and the landmark.

Back Bearings

You can also take a back bearing from such a landmark—useful if you’re not sure of your position. This can be done by repeating the above process, except “boxing” not the north end but the south end of the compass needle with the orienting arrow, then reading the degrees where the direction-of-travel line hits the dial.

Or you can just measure a direct bearing and then—because the back bearing is simply the very opposite of it—either subtract 180 degrees (if the direct bearing reads 180 or more degrees) or add 180 degrees (if the direct bearing reads less than 180).

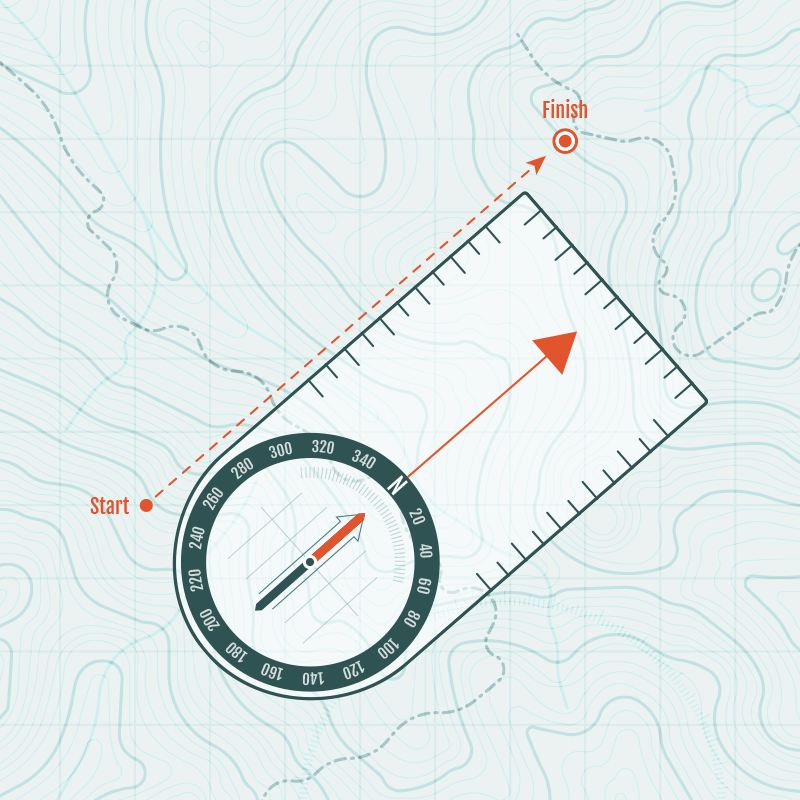

Measuring Bearings on a Map

Measuring direct or back bearings from visible landmarks with a compass alone relies on the magnetized needle. But if you want to take bearings from a topo map—in other words, find a course—you actually completely ignore that needle (not to mention declination) and simply use the baseplate compass’s rotating bezel. Here’s where the baseplate compass serves essentially as a protractor.

Place the compass flat on the map with the travel arrow pointed in the general direction of north and one of the base plate’s long edges linking your location and your destination; you may need a straight-edge to make the connection, depending on the map’s scale and the distance to be covered.

Then turn the housing so that its meridian lines run parallel to the north-south grid lines of the map (1). Identify the bearing where the index line meets the dial (2).

How to Use a Compass to Plot Bearings in the Field

If you’ve taken a bearing (or found a course) from a topo map (1), you can steer yourself along with it by holding the compass level, then turning your body (2) so that the needle’s boxed by the orienting arrow (3). When that happens, you’re facing your destination (4) with the direction-of-travel arrow pointing (5) the way to go.

You can, of course, use this method to follow a course from any known bearing, not just a topo-taken one. For example, a guidebook (or experienced buddy) may give you precise directions to a dispersed campsite or a water source somewhere out of sight but reachable by following a bearing from a certain location on the trail.

Turn the azimuth ring to set that bearing at the index line and follow the same procedure to orient yourself and strike off.

Use a Compass to Plot Bearings on a Map

You can also plot a known compass bearing on the map—the reverse process. This may arise when you don’t know your current position but have taken a back bearing from a visible landmark (1) you can identify on the map. Turn the compass dial so that the bearing intersects the index line (2).

Then put the base plate on the map with one of the front corners on the mapped landmark. Turn the whole compass until the meridian lines lie parallel with the map’s north-south lines. This gives you a position line (3) along which you know you are.

If you’re hiking a trail or following a river or ridgetop or otherwise situated along with a mapped linear feature, that position line revealed by your field back bearing will pinpoint your location.

Crisscrossing Position Lines & Contours

If you aren’t along with such a reference feature, you can still fix your position by taking one or more additional back bearings from other mapped landmarks (as far apart from one another as possible) and drawing position lines from them on the map. Your point position is where those position lines cross.

Maybe, though, you can only recognize one landmark you can definitely locate on the map. You can often still get some idea of your rough location by identifying your elevation using an altimeter and seeing where the position line crosses that particular contour.

Obviously, it may cross multiple contour lines of that elevation, but cross-referencing with other topographic or geographic features will hopefully narrow down the possibilities.

How to Use a Compass to Locate Yourself With a “Running Fix”

You can also try to mark your general location from a single mapped landmark by obtaining a “running fix,” as mariners use in nautical navigation.

Here’s the process (nicely laid out in David Seidman’s much-recommended The Essential Wilderness Navigator):

- Take a back bearing from the landmark and draw your position line, then walk a straight line (aided by your compass), keeping some rough track of the distance you’re covering until you reach a point where another back bearing taken from the landmark is at least 30 degrees different from the first.

- Draw that bearing line on the map.

- Put a straight-edge parallel to your course that intersects both position lines, and slide it along the map until the distance between the two lines, as gauged by the map scale, matches (more or less) the ground you covered between taking the two back bearings. You’re about where the straight edge hits the second position line.

Finding & Identifying Landmarks

The same principles we’ve outlined above can easily be used to find a mapped landmark on the landscape or, conversely, identify visible distant objects on the map. Mountain peaks or major hilltops are obvious examples.

Identifying a mapped summit in a sea of peaks from some known vantage is the same as matching a bearing measured on the map to the field; sight along the set course, and you should be looking at the peak in question.

And all it takes to I.D. an unknown peak—assuming it’s named or at least labeled with elevation on the topo—is to take a bearing off it and then plot that on the map.

Using Your Compass to Orient Your Map

Depending on how your brain visualizes things, you may get along just fine studying your map with the top of the chart always pointing up. But some navigators prefer orienting the map to the landscape, which also may be necessary for the particularly confusing countryside.

Sometimes it’s easy enough—and, from an orientation perspective, good enough—to simply turn the map to conform to the arrangement of obvious, recognizable, mapped landmarks in view. But if you can’t identify surrounding landmarks, or if you want to be as accurate in orienting your map as possible, use your compass.

Turn the dial so that the ring’s north marker (0 or 360 degrees) hits the index line (1). Then place the left or right edge of the base plate along the analogous margin (2) of the topo—placed on a flat surface—with the direction-of-travel line pointing toward map north (3), and turn compass and map together until the orienting arrow boxes the north-pointing needle. The map’s oriented to the landscape as you see it.

Following a Compass Course

The trick to following a compass course long-distance is to use intermediate destinations along the desired bearing to keep you on track toward your intended destination. You may or may not have your destination in view when you begin following your bearing: maybe you can see a particular peak or lake, but maybe you’re trying to navigate to that out-of-sight, possibly fairly far-off campsite from the trail.

But unless you’re trekking across open, fairly level tundra, steppe, or desert, you’re not likely to have, say, a target peak in view the whole way—not when you’re traversing dense forest or dropping into valleys or ravines along the bearing, or entering ranges of foothills before hitting the ultimate slopes you want.

It’s impractical, too, to keep your compass out the whole hike, following the direction-of-travel arrow and keeping the needle boxed. It doesn’t make cross-country travel very easy, for one thing, and you’re just about guaranteed to stray to one side or another of your desired course.

You can drift laterally this way and still find your compass reading the proper bearing, though following it won’t get you to a destination point. And, of course, you’re very likely to hit obstacles along the way that force you to detour.

Using Intermediate Landmarks to Follow a Compass Bearing

To embark on your course by sighting down your desired bearing and locating a near-range landmark, such as a rock formation (1), a lofty tree (2), or a big log, along with it. Then you can simply walk whichever way is easiest to the landmark.

Repeat the process by sighting ahead along your bearing and finding another strategically positioned landmark. By doing this, you’ll stay true to your course and you won’t have to be referencing your compass all the time.

Making use of intermediate landmarks is even more reliable when you take back bearings along the way to previous “waystations” to check that you’re headed in the right direction.

Dealing With Obstacles Along a Compass Bearing

You’ll often need to be negotiating obstacles—lakes, swamps, impassable terrain, nasty stretches of blowdown, and the like—when following your compass course. If you can see across the obstacle and there’s a landmark on the other side along your bearing line, just work your way around and get to that touchstone so you can resume your course.

If there isn’t an opposite-side landmark but you can easily identify your starting point in detouring, get to the other side and take a back bearing from the starting point.

If you can’t see across the obstacle or you don’t have any reference points to use on either side of it, execute your detour by making right-angle turns and counting your steps along with straight-line courses between turns—however many are required to get around.

By compensating for your side-tracking with an equal number of steps in the opposite direction on the other side of the obstacle, you should be able to exactly resume your course.

Another Wayfinding Trick With the Compass: Aiming Off

A very important practice to learn as a backcountry traveler is what’s known as aiming off or international offset. This is a safety-net procedure to allow you to navigate back to a starting point located along a baseline of some kind. For example, you might want to return to a vehicle parked along a road, or to a campsite along a trail.

You’ve followed a bearing on your hike from the starting point, and now want to get back to that car or that campsite. You could follow the back bearing exactly, but you’re invariably going to drift a bit, and then when you hit the road or the trail you won’t know which way to turn to get to your destination.

So instead of following your return bearing exactly, you “aim off”: that is, you intentionally hike significantly to one side or another of the exact course—by more than just a few degrees. Veer off by, say, 10 to 20 degrees, enough to ensure that when you intersect the baseline, you’ll know for sure you’re to the right or the left of the starting point, and thus be confident which direction to go.

Negotiating Obstacles While Aiming Off

Effectively aiming off requires that, should you hit an obstacle on your return hike, you always detour to the offset side you’ve chosen to maintain the correct direction. If you’re heading northeast to reach a campsite roughly due north, for example, and you hit a tangle of deadfall, you should go bypass it by angling around to the east.

Put in the Field Practice to Master Compass Navigation

Reading about the ins-and-outs of using a compass correctly is all well and good, but it won’t get you very far: You need to invest plenty of quality time in practicing out in the field. Start with your neighborhood, maybe your nearest city park; then graduate to more “real-world”-style map-and-compass exercises out in the woods.

Before long, sighting and plotting bearings will become second nature—and, more magically yet, you’ll find yourself striding with genuine confidence out into big, trackless backcountry, feeling firmly centered in—and all the more connected to—the landscape around you.